After an initial enquiry in March 2018, the North West England Fibreshed became an affiliate of Fibershed.org in May 2020.

Now, 6 months later, I’m reflecting on these first preparatory months and am opening up this ‘News’ feature on our (yet to be officially launched) organisation website. Over the coming weeks, this will become a place where our producers can share how they’re working with (or working towards) the high standards of textile/fashion production stipulated by the Fibreshed ethos.

This first post is an introduction from me, Justine Aldersey-Williams, Regional Coordinator and founder of this affiliated branch. In addition to this role I am a textile designer and teacher at The Wild Dyery, specialising in natural fabric dyeing.

I’m happy to admit, I’ve been on a steep learning curve since founding this Fibreshed and want to speak to other textile professionals like me, who might not have a background in farming or sustainable fashion, because there should be no barriers to getting involved in this much needed movement.

So, if you know a little about Fibreshed, enough to know you want to get involved but feel a bit daunted by all the new concepts and terminology, what follows is an absolute beginner’s guide, including an overview of what a Fibreshed is, why I’m volunteering and what our community hopes to achieve.

What is a Fibreshed?

If you’ve never heard of a Fiber/Fibreshed (spelling dependent on where in the world you are) here’s the official definition:-

“A Fibershed is a geographical landscape that defines and gives boundaries to a natural textile resource base. Awareness of this bioregional designation engenders appreciation, connectivity, and sensitivity for the life-giving resources within our homelands.” – fibershed.com

The Fibershed strap line is ‘local fibres, local dyes and local labour’. As an ethos that remembers our indigenous past, when humans better understood their place within our ecosystem so lived in harmony with natural resources, it should be profoundly simple to implement. Yet when placed within the context of a globalised, capitalist, colonialist economy, this simple strap line exposes how distorted our way of living has become and the challenges we face changing things.

In the midst of climate breakdown, the fashion industry continues to be one of the world’s main polluters, driven by our economy’s need for perpetual growth from finite planetary resources.

While our U.K. industry has been decimated by offshoring, garment workers in the global south are forced into slave labour and suffer the worst effects of environmental pollution. It’s a lose-lose situation for everyone involved, including the consumer who buys poor quality, cheap clothing, only to have it perceived as ‘out of fashion’ after one wear, upon which it will likely fall apart and be discarded anyway.

- 70% of all clothing is derived from polluting petrochemicals¹

- 60% of all clothing produced is disposed of within the same year it is purchased² creating a truck load of waste per second³

- In the past 50 years, employment in the U.K. textile industry has dropped from 1.6M to 50K causing social deprivation particularly in N.W. England⁴

- In 2013, 1134 garment workers died in Bangladesh after an unsafe fast fashion factory collapsed⁵

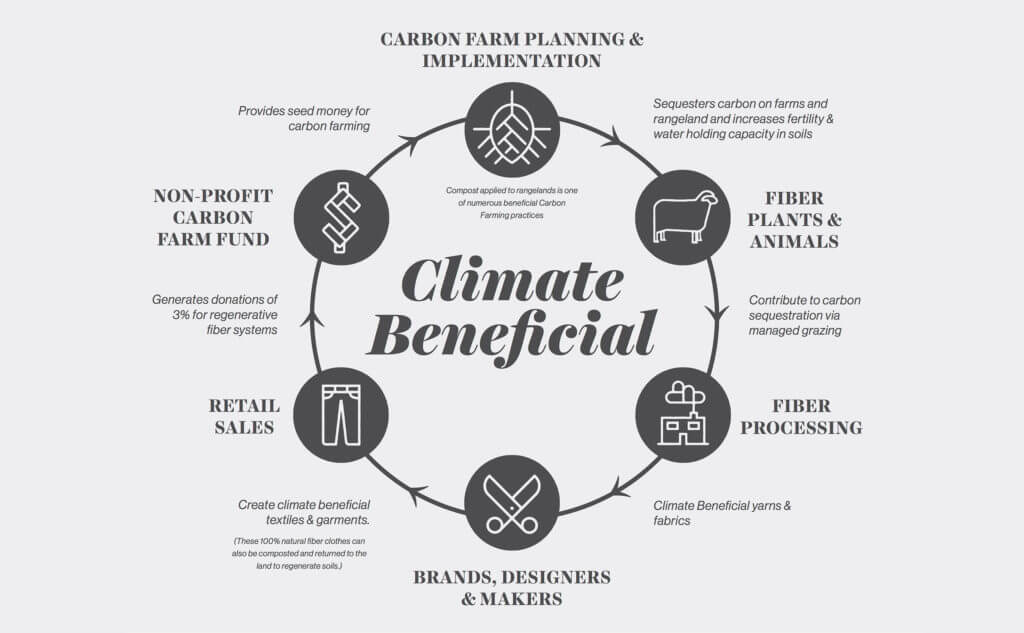

Fibershed is fast emerging as the highest standard for a new fashion industry that remedies social and environmental exploitation by empowering regional economy and ecology.

Imagine a reshored textile manufacturing system that starts with regeneratively grown fibres and dyes, offering farmers additional income while building healthy soil and biodiversity. A system that is framed within the ‘post-capitalist’ principals of ‘Doughnut Economics’ and produces clothing (and employment) in a fully traceable way that eliminates environmental and social exploitation.

Fibershed are making this a reality and we’re not alone. I’d recommend watching the film ‘Kiss the Ground’ for more information about how regenerative crops (including textiles) could quickly help reverse climate breakdown. Also, the film ‘Gather’, which highlights the role indigenous caretakers have played in preserving our remaining biodiversity, while guiding humanity back into reverence for our planetary life-support system, Mother Earth. For a broader context on why localisation is crucial, another film ‘Economics of Happiness’ by the incredible team at Local Futures (who also have a site full of brilliant resources) is a must.

Why I’m Volunteering

As the great poet and civil rights activist Maya Angelou said, ‘when you know better, do better’. I was lucky enough to be immersed in eastern philosophy for 12 years as a professional yoga teacher prior to resuming my career in textiles. Whilst there are undoubtedly cultural appropriation issues in the way this wisdom has been interpreted by western society, I am grateful to have been guided to a sense of union with all of life that has deeply affected how I work.

This feeling of yoga (root ‘yug’, meaning to yoke or unite) is hard to describe unless you’ve experienced it, yet it naturally engenders reverence for all living beings; human and non-human. It homes people in the elemental truth of who they are; earth, air, fire, water and spirit, in a way that echoes the beliefs of indigenous cultures all around the world. Once this remembrance of the Earth as our bigger, life-sustaining body has been realised, it becomes impossible to destroy.

For me, this awareness has completely dictated how I work. After setting up my natural dyeing company The Wild Dyery in 2015, at a time when horrific revelations about the climate crisis were emerging every day, I decided to stop making and selling textile products. I felt there was already enough stuff on the planet and couldn’t trace my supply chains or guarantee I wasn’t promoting social and environmental exploitation. Instead, I decided to teach botanical fabric dyeing online and at my studio, in the hope that it would encourage people to revive their old clothing with natural dyes, as a way to slow the consumption of fast fashion.

I also became a volunteer for the global reforestation charity, TreeSisters and donate a percentage of profits from my online courses to tree planting initiatives. But when I became aware of Fibershed, I started to see a way I might one day be able to create textiles within a system that helped the environment and it gave me much needed hope!

Illustration by Andrew Plotsky.

I still offer a comprehensive online training in natural fabric dyeing but hope one day to be able to get creative with natural fibres and dyes grown in my region. The only way I see this happening is by volunteering as an affiliate for Fibershed. I have an exciting challenge ahead, but am already collaborating with some exceptional people who feel just as passionately as I do about this cause.

What does N.W. England Fibreshed hope to achieve?

Since the 1400s, the North West of England has been a world renowned centre for textile manufacturing. In 1821, Manchester alone had 66 cotton mills⁶ and even today, 3/4 of the country’s textile processing facilities are in the North West.

We have an incredible textile heritage that still defines our communities and landscapes, but which also carries the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade that fuelled colonialist capitalism and as a result, the social and environmental crises we face today.

Could a regenerative Fibreshed system repair some of the damage caused?

I believe so.

Right now it might seem impossible, but this is the aspiration of a growing number of textile professionals based in Cumbria, West Yorkshire, Lancashire, Greater Manchester, Merseyside and Cheshire, who aspire to use regeneratively grown fibres and dyes.

I hope this has been a useful introduction to our new Fibreshed. Over the next few weeks, producers already listed in our directory will introduce themselves and their work. There will also be news of some exciting projects happening in our area. If you are based in the region, work with natural fibres and/or dyes and want to join our community, please get in touch.

References:

¹ http://fibershed.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Fibershed-Clothing-Guide-first-edition.pdf

² Remy, N., Speelman, E. & Swartz, S. Style That’s Sustainable: A New Fast-Fashion Formula (McKinsey&Company, accessed 11 December 2017)

³ A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017)

⁴ https://communityclothing.co.uk/blogs/news/a-letter-from-patrick-grant-founder-of-community-clothing

⁵ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2013_Dhaka_garment_factory_collapse

⁶ https://www.englishfinecottons.co.uk/journal/heritage/potted-history/