A lot has happened since August 13th when a group of around 30 volunteers came to Higher Audley St in Blackburn to help pull and lay out our flax. It now feels like years ago but with 2022 looming, this seems the perfect time to remember the field to fabric stage of the Homegrown Homespun project.

On harvest day, we were live on Radio Lancashire and also had a brilliant time with BBC Radio 4’s Heather Simons and Ian Marchant recording ‘A Fabric Landscape’ – a programme dedicated to the Homegrown Homespun project which is available to listen to online.

Ian had previously discovered a diary from a 17th Century ancestor who worked in the linen industry, so had a special interest in our quest to reintroduce this heritage crop. He had a go at extracting woad pigment, breaking scutching and hackling some plants into fibre and especially enjoyed fashioning and modelling his own flaxen haired wig!

From Seed to Sewing Bee

Meanwhile, I managed to coax Patrick into a pair of marigolds to try some natural fabric dyeing after explaining a vision I’d had of him wearing a homegrown, hand-dyed hankie and us perhaps one day spotting him on TV with a little piece of our Blackburn indigo. I imagined our team would share a smile remembering the day we all stood in a field and mashed leaves into cloth together during our first ever harvest. As mentioned previously, I knew our woad crop had mostly failed but wanted to use what we had to share the fun of natural dyeing. It’s all too easy to write off disappointments as failures, missing other opportunities, so I bought some British peace silk and asked my mum (who loves hand stitching!) to roll the hems on 3 pocket squares/hankies. We used the fresh leaf salt rub dyeing method and discovered the unique shade of Blackburn Woad.

N.B. The fresh leaf salt rub method creates a teal rather than classic indigo blue due to other pigments such as chlorophyll and indirubin present in Woad leaves prior to extraction.

I subsequently hand embroidered each with the impromptu HH logo that emerged when dyeing aprons for our workshops and each project partner’s name, using indigo dyed thread, hurriedly posted his off to him in his 10 week filming bubble and sure enough, my vision was manifest – he wore it during the Great British Sewing Bee Christmas Special which aired on BBC 1 last week and we all tuned in and remembered standing in a field in Blackburn, mashing woad leaves into silk together during our first ever harvest.

Extracting Fibre and Dye

In the 10 weeks between harvest and the end of October when we were to showcase our results, we accomplished what we’ve since realised was a astonishing feat. Learning on the job, we discovered that flax farmers usually overwinter their crops to dry thoroughly following a 2-6 weeks retting, yet we had only 10 weeks to complete the entire plant to cloth process. Herein lay our compromise and challenge. We were advocating regenerative, slow fashion and textiles, yet had a great opportunity to raise awareness of these ideals by rushing to meet the exciting deadline of the British Textile Biennial – which we did, with a few edits and sleepless nights!

Retting was the first stage and it became evident that this is one of the crucial keys and skills (we didn’t yet have!) to a successful fibre crop. There was a panic due to large variances in our stem thicknesses, causing some stems to have rotten after just 2 weeks. We were advised to stook (see above) the entire crop and get it undercover. Better to be under retted than over! Our 5kg of seed yielded 96 stooks – a few of which were sent to Simon at Flaxland for processing. The rest are being stored and will go towards the stock needed for our 2023 upscale.

In addition to extracting fibre, I also needed to release the mystical blue dye from within our woad and Japanese indigo plants and it was great sharing this magical process with our volunteers.

Growing Slow Textiles

I can’t fully verbalise to those who haven’t experienced indigo pigment extraction and dyeing, just how miraculous it feels to see blue appear on fabric or yarn from green leaves you’ve grown yourself. What I can do is offer you a chance to share the experience with me next year as I’ll be guiding a group through a 9 month ‘Growing Slow Textiles’ holistic immersion into flax and indigo. Details to follow but for now, if you click the link, you can join a holding page on Instagram where I’ll announce it soon.

British Textile Biennial

On an incredibly tight schedule, coordinating a team in various parts of the country, our flax plants were hand-spun in time for the start of the month long British Textile Biennial last October. This took Carole Bowman (weft) and Amanda Hannaford (warp) about 70 hours over 3 weeks.

The weft yarn had arrived the day before it was due to be dyed, so got a swift but vigorous double scouring as I prepared materials for the workshop. I don’t think anyone realised as they were all enjoying indigo dyeing wrapping cloths but my face dropped when the HH weft came out of the vat! It was changing colour only slightly – a lot less than usual. It evidently hadn’t scoured enough – had it been under retted so still clinging to some of its lignins and pectins? I spent another day after the workshop re-scouring and dyeing so it was just right for the weavers to start the following Wednesday.

Weaving Warp and Weft

We’d amended from an adult pair of jeans, to toddler sized dungarees based on the time our spinners could allocate, yet once the weaving started new challenges presented themselves. Even with a £15K state-of-the-art loom kindly provided on loan by MMU and two of the best weavers in the country, Kirsty McDougall and Sally Holditch, it proved incredibly difficult to weave with our homegrown, hand spun linen warp. I’m not a weaver and the terminology baffles me but words I do understand like ‘sticky’ ‘fluffy’ and ‘tangled’ were used a lot – along with some expletives! However, the ‘ends per inch’ were adjusted, prayers and incantations uttered and by some miracle of talent and persistence, cloth was woven.

Brave Beetling

A decision then had to be made whether to risk subjecting this fragile cloth to the vigorous beetling process which in this case would involve dampening, then pressing and rolling with a pipe or wooden rolling pin. This transforms ‘loom state’ warp and weft into a coherent, draping cloth. Opinions were divided – so we went for it! How else would we know the cloth’s potential?

Our Historic Cloth

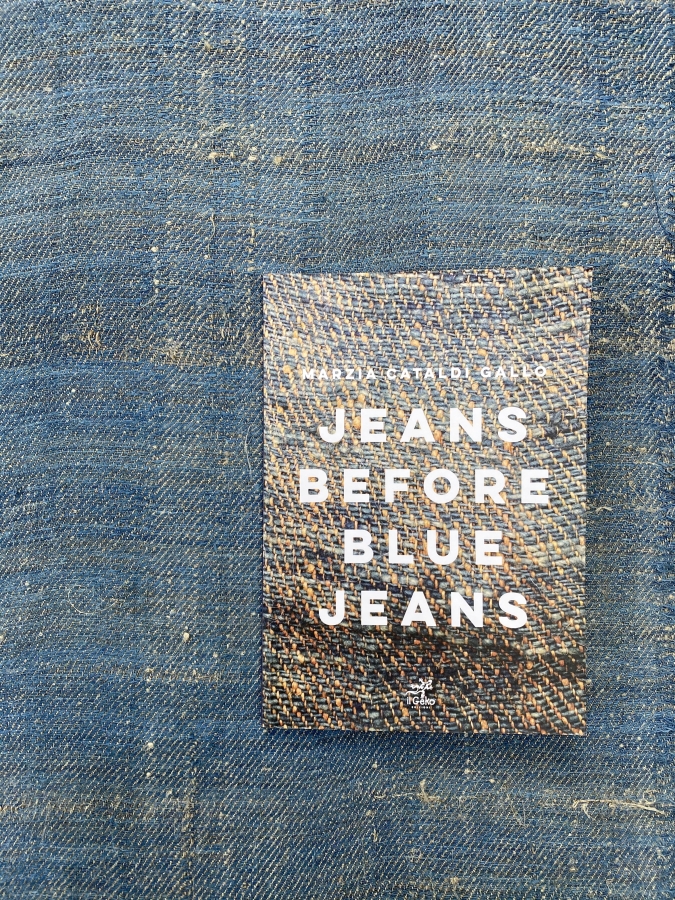

Having thought we’d developed a unique, hand spun cloth, we were stunned to discover a newly published book ‘Jeans Before Blue Jeans’ by Marzia Cataldi Gallo showing an almost exact version of our denim on the front cover. This caused us to pause for thought about the significance of what we’ve made and reconsider cutting into it.

Denim consultant, historian and lecturer at Central St. Martins and the Royal College of Art, Mohsin Sajid commented, “this is a watershed moment in the industry. I believe you are the first to home-grow indigo linen denim, at least since Levi’s introduced synthetic indigo in 1897, if not longer, so you should be really proud. You’ve proved the concept and raised so much awareness about how hard these processes were and how much we take fabric for granted.”

Despite one of the purposes of Homegrown Homespun being to eventually bring indigo linen jeans to market, we decided to let the uncut material speak for itself. Patrick requested I embroider the outline of a trouser leg pattern to indicate our intent and acknowledge how far we got in our original quest.

The cloth is being exhibited in Blackburn Museum until 16th January 2021, so if you can, go along and see it.

Spreading the Word

I’ve been asked to speak about my work on the HH project quite a bit lately so am including links to catch-ups. I was interviewed in episode 4 of Amber Butchart’s ‘Cloth Cultures’ podcast about linen and was then part of the Making Matters x Levi’s Digital & British Council panel discussion she subsequently hosted at Blackburn Cathedral. I took part in the (unrecorded) Fashion Open Studio COP 26 event, ‘Renaturing Fashion’ and the RSA’s ‘The Evolution of Fashion’.

I’ve also been a guest speaker and lecturer at Tauheedul Islamic Girl’s School, Blackburn College, Liverpool John Moore’s University and Edge Hill University’s Sustainability Festival.

Making Provenance Fashionable

So, to summarise this first 2021 phase, the Homegrown Homespun indigo linen denim is 100% made in England with the blue weft yarn being the produce of our first flax and woad harvest this year in Lancashire. Our deliberately ambitious plan to grow an entire pair of jeans sought to expose the difficulties of working ethically and sustainably in a country with no facilities to process its native arable textile crops.

To highlight the fashion industry’s huge potential to sequester carbon from our over-heated atmosphere back into our depleted soil, a team of experts and volunteers worked entirely by hand; growing, spinning, naturally dyeing and weaving the way our ancestors did. We sought to prioritise the regeneration of our local environment and the people who rely upon it, so willingly adapted and amended our outcome to reflect the many lessons that coming back into balance with the ecosystem offers humanity.

The shift in human behaviour needed to evolve from being an extractor species to a restorer species means the fashion industry must also shift from selling products regardless of their provenance, to instead making ethical, regenerative processes fashionable. As Fibershed help launch #MakeTheLabelCount we see the emphasis shifting away from the veneer of a deceptive product advertising campaign to purchasing decisions based on supply chain transparency.

We believe this cloth epitomises the beautiful struggle of all those involved who are committed to ‘being the change’. The love and hopes of so many are woven into this humble fabric and the task now begins to create the midscale facilities required to upscale to full production via Community Clothing in time for the 2023 British Textile Biennial.

“Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.”

― Arundhati Roy